The South African retail sector is often celebrated as a bellwether of the mainstream economy: ubiquitous, capital-efficient, and central to everyday life. It is also a mirror of our unfinished transition. From the vantage point of industrial sociology and critical transformation studies—and as a member of the Black Management Forum (BMF)—the question is not whether progress exists, but whether it is structural, durable, and proportionate to our democratic horizon.

Two realities can be held at once. First, some governance gains are visible at the board level across major JSE-listed retailers. Second, the composition of executive leadership—the locus of real operational power—remains stubbornly out of step with the demographic and developmental imperatives of a just economy. This divergence is not incidental; it is symptomatic of how transformation has been managed as optics first and operating model last.

Below, is a reflection on what the data implies about the sector’s transformation trajectory, why form keeps outrunning substance, and what must change to convert representation into power, and power into outcomes.

The two-tier equilibrium: diverse boards, homogeneous executives

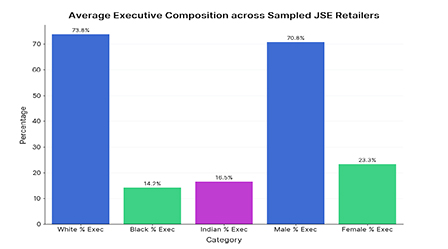

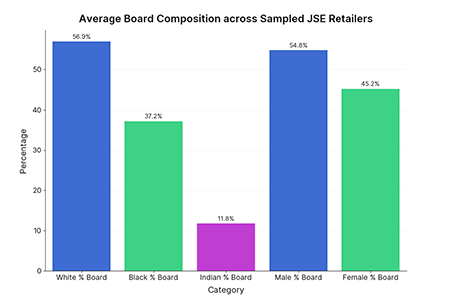

Across a sample of top JSE retailers, the average board shows far closer movement toward gender balance and increased Black representation than the executive benches beneath them. The visual summaries below highlight a pattern the BMF has tracked for years: governance-level inclusion outpacing C-suite and executive control. These figures are not merely about optics; they map where decisions actually get made.

Average executive composition across sampled retailers:

Average board composition across sampled retailers:

These charts reflect a persistent transformation “gradient.” Boards—where visibility is high and cadence of change is slower—are more representative than executive teams—where daily choices on capital allocation, procurement, pricing, store networks, and labour are made. In an economy where retail is a major employer, that gradient is consequential.

The logic is simple. A board with balanced representation can set the tone, but it is executives who translate strategy into incentives, headcount, and supplier development. When executives remain demographically skewed, value chains do too: who gets promoted, which stores open and where, how supplier credit terms are set, and how risk is framed. The democratic dividend gets diluted in the pipes of the organisation.

The cost of superficial transformation

Industrial sociology teaches us that institutions reproduce themselves through routines, incentive structures, and networks of trust. Where executive compositions remain predominantly White and male, you often inherit:

Narrow recruitment networks that perpetuate homogeneity at the level below (GM, regional, and functional heads).

Risk framings that prioritise legacy suppliers and familiar capital over emergent Black-owned suppliers and township-based ecosystems.

Reward systems that valorise tenure and cultural fit over transformation impact and pipeline building.

This is how you get “diversity at the edges, continuity at the core.” It also explains why ESG reports may show improved governance metrics while supply chains and mid-management pipelines still lag. Such gaps are not only ethical failures; they are missed strategic arbitrage. South Africa’s demand growth over the next decade sits disproportionally in Black urban and peri-urban markets, in women-led households, and among micro-entrepreneurs who are both consumers and producers. A leadership cohort that does not reflect or embed itself in these markets will allocate capital suboptimally.

Gender parity is a necessary condition, not a sufficient one

The data indicates greater movement on gender at board level than within executive roles. Retail historically touts high female representation in its workforce, yet this has too often been trapped at the base and middle of the pyramid. Real transformation requires three things simultaneously: representation, authority, and budget. If women’s representation rises at board level but stalls in P&L-owning executive roles, the organisation remains structurally male in its value-creation engine. That is not a glass ceiling; it is a glass operating model.

Race dynamics: why “partial progress” becomes an alibi

The pattern of Black representation improving faster on boards than in executive roles reflects a deeper organisational psychology: it is easier to adjust the visible apex than the hardwiring of everyday power. But real economy outcomes emerge from procurement thresholds, store-level operating models, logistics contracts, and credit policies—none of which change without executive accountability.

From a BMF standpoint, we must retire the comfort of partial progress where it matters least. A board-level shift that is not matched with intentional, time-bound, and measured executive diversification is not transformation; it is choreography.

What good looks like: from compliance to capability

There are retailers in the sample whose boards are now meaningfully balanced in race and gender terms. That is a platform. The next leap is capability-oriented:

Tie executive scorecards to measurable outcomes: internal promotion velocity of Black and women leaders; procurement share to Black- and women-owned suppliers; and store network expansion into underserved geographies with local ecosystem partnerships.

Make succession planning a quarterly operating ritual, not an annual box-tick. Every executive seat should have at least two successor candidates, one of whom must be from an under-represented group and on an active development plan with exposure to P&L decisions.

Rebuild recruitment pipelines through structurally different networks: historically Black universities and technikons, professional bodies like ABASA and BMF chapters, and sector-focused accelerators for retail analytics, logistics, and merchandise planning.

Redesign incentives: a meaningful proportion of long-term variable pay should vest only when transformation milestones are achieved at executive and VP levels, not just in governance optics.

The policy and investor angle: signal what matters

Policymakers should align procurement and licensing regimes to reward retailers who move beyond board optics into operational control transformation. Investors—especially pension funds and development finance institutions—must explicitly price transformation execution into cost of capital and engagement intensity. Stewardship must become transformation-literate: engagement letters that probe the composition of the EXCO, internal promotion rates, and supplier inclusivity—not only carbon and audit quality.

For listed retailers, the most credible disclosure now is not the static percentage on a page, but the velocity of change across three years, disaggregated by function (merchandising, logistics, finance, digital) and power (budget ownership). Show us the pipeline, the moves, and the money.

Why this matters now

Retail is the public face of the economy. When its leadership does not reflect the nation, it normalises exclusion at scale. When it does, it changes who gets mentored, who gets financed, which products make the shelf, and how the consumer is dignified. In an environment of low growth and high unemployment, this is not a moral luxury; it is an engine for new demand, innovation, and legitimacy.

Thirty years into democracy, we can no longer accept a transformation curve that flattens precisely where power concentrates. The data tells a story of partial convergence at the top and drift in the operational core. The work ahead is to reverse that gradient: make the executive the sharp point of change and allow the board to be its steward, not its substitute.

The BMF position remains clear: transformation is not an HR project or a governance paragraph—it is industrial policy executed inside the firm. The retailers who embrace that truth will secure social permission, tap unmet markets, and outperform through cycles. Those who do not will find that in South Africa, the market is not an abstraction. It has a face. It expects to be seen. And it remembers who showed up.

References

Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act (B-BBEE) and Codes of Good Practice, DTI.

King IV Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa, IoDSA.

BMF Policy Position Papers on Executive Transformation and Supplier Development, various years.

Stats SA Labour Market Dynamics and Living Conditions Surveys (for demographic and gender context).

Annual integrated reports of sampled JSE retailers (governance and remuneration disclosures).

Monde Ndlovu

BMF | Managing Director