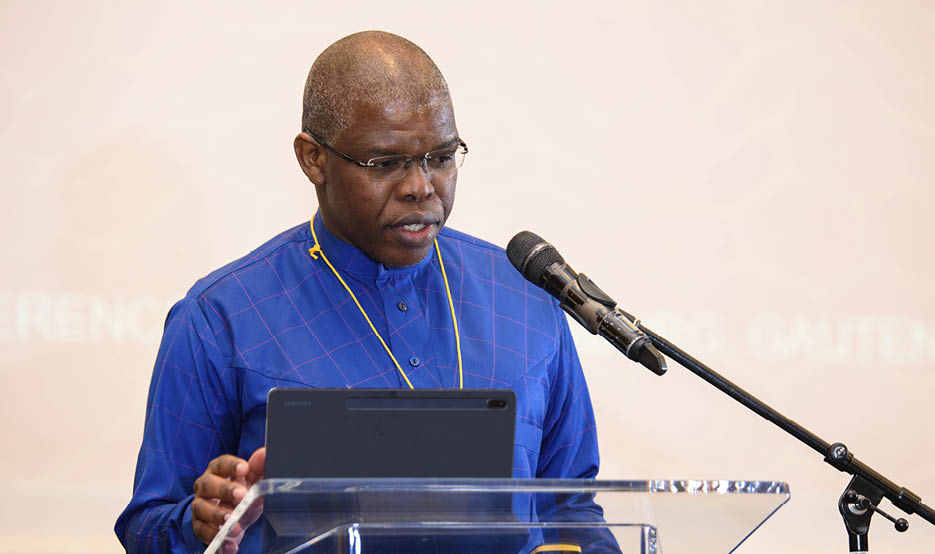

The economic transformation

trajectory has

escalated in the

past 30 years

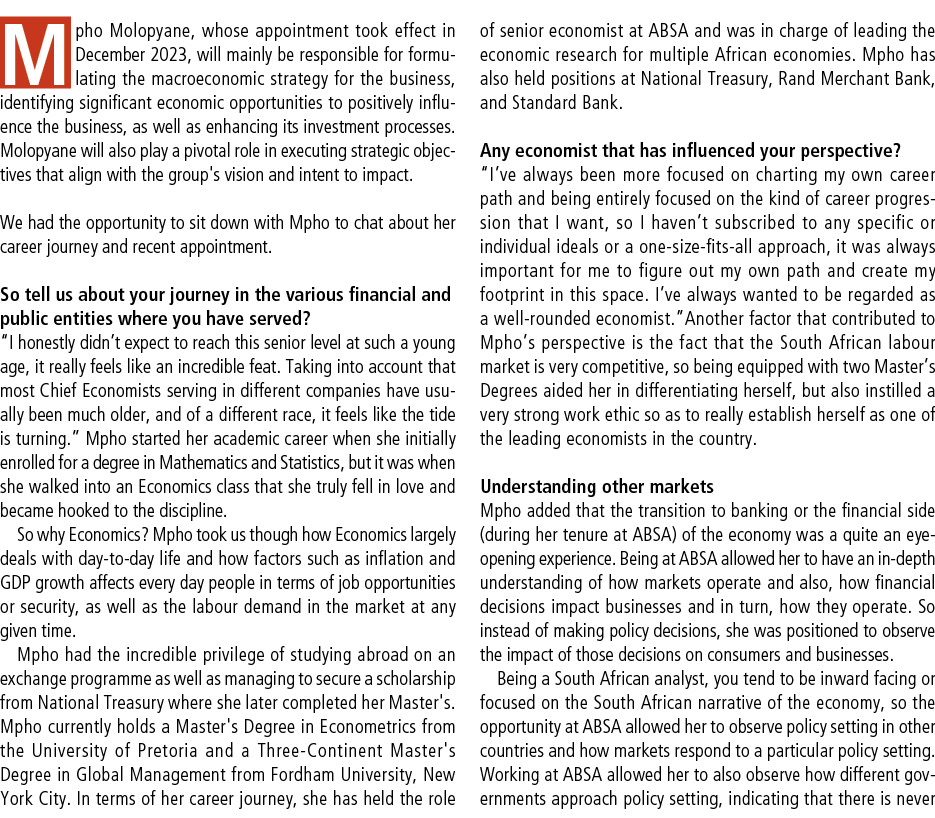

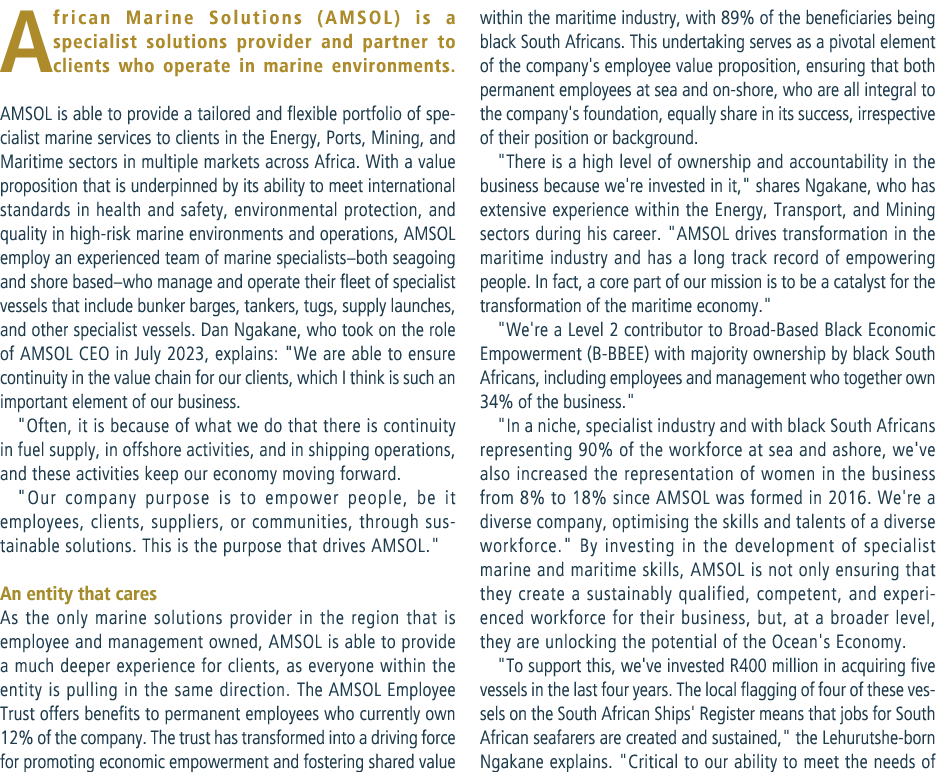

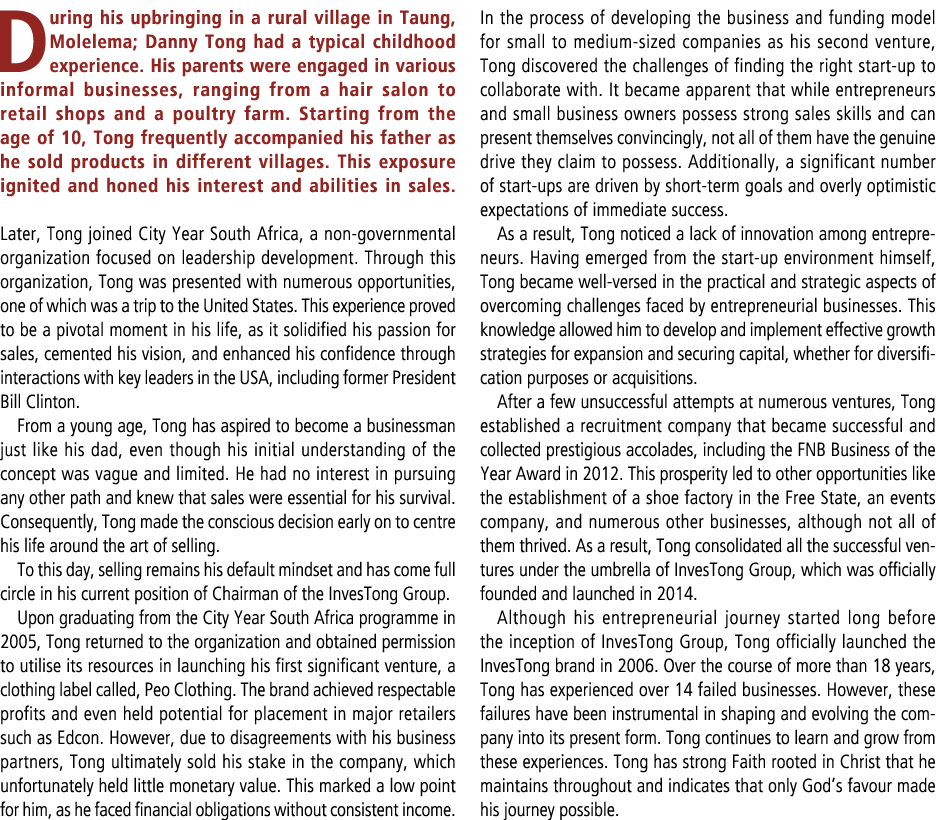

In 1994, the South African society and its economy was deeply fragmented, racially divided and associated with a slow pace of growth. It was managed through a repressive regime of regulatory restrictions and limitations, which effectively recognized white male dominance and supremacy. Thabo Masombuka provides a 30 year reflection.

30 years later, on the 7th of February 2024, the country's President CR Ramaphosa delivered what others have arguably dubbed his "last state of the nation address (SONA)”. In his address, he outlined and boasted about what he described as “the positive progress made by the ruling party in advancing the national democratic revolution and changing the economic face of South Africa”. This would later be described in some corners as an “economic Tintswalo” phenomenon. Could it really have been?

Although it remains debatable whether the true state of economic transformation can be measured through acceptable social scientific means and evidence. A week after the SONA, StatsSA's last quarterly results of 2023 showed that the numbers of unemployment had risen up to 32.1%, making SA a country with one of the highest unemployment rate in the world. Employment opportunities and employability, economic growth and development, access to finance, and funding of concepts are important measures and yardsticks in determining the extent of progress made in the economy of every nation.

For this reason, the conversation about the state of economic transformation and inclusion cannot be complete without a closer look at the main and major policy frameworks that have been developed to fast-track and facilitate the participation of black people and professionals–namely, BBBEE and Affirmative Action.

BBBEE was meant to–in the bigger scale-facilitate the transformation of the mainstream of South Africa’s economy to ensure that it includes the section of the communities that not only were previously prohibited and excluded from participation, but were also inadequately equipped (through Bantu Education), to participate in any form of economic activity.

Undoubtedly, those sections of the society happened to have been the majority of the citizens (over 81%) who are black and living in advent poverty. Black is defined as Africans, Coloureds, and Indians (The ACI)–in that particular order. Through the BBBEE strategy that was published as a precursor to the BBBEE Act, No. 53 of 2003, the government would have had to take a leading role in advancing economic transformation and enhance the economic participation of black people in the South African economy. This was the moral and constitutional fundamental and imperative.

Black Economic Empowerment policy would therefore be South Africa’s torch-bearing instrument in facilitating broader participation in the economy by black people and all citizens. Together with affirmative action, BBBEE would redress the inequalities created by apartheid and racism. The policy would provide for incentives–especially preferential treatment in government procurement processes–to businesses which contribute to black economic empowerment according to several measurable criteria, including through partial or majority black ownership, hiring black employees, and contracting with black-owned suppliers. The preferential procurement aspect of BEE has been viewed as paradigmatic of a sustainable procurement approach, whereby government procurement is used to advance social policy objectives.

Having obtained political power in 1994 and constitutionally entrenched rule of law in 1996, there is certainly no doubt that the ruling party took over and inherited a fragmented, divided economy that was isolated by the international community as a result of the sanctions and UN restrictions.

The 30-year (then) comparison of 1994 and 2024 will always be symbolic, sentimental, and structural in interpretation, depending on how you want to look at the progress of the South African economic transformation trajectory. It is therefore imperative to do the comparison having regard to the following; 1) the size in population between then and now, 2) the rate of economic participation and growth between then and now, 3) the legal permissibility between then and now, the industries and economic sectors available between then and now. What is even realistic is that over the last 30 years, the country’s population had risen by a whopping 17 million plus citizens from 43.27 million then, and 63 million now. The latter figure includes a significant number of immigrants from the neighbouring countries of SADEC. Therefore, a transformed economy would have taken these factors into account.

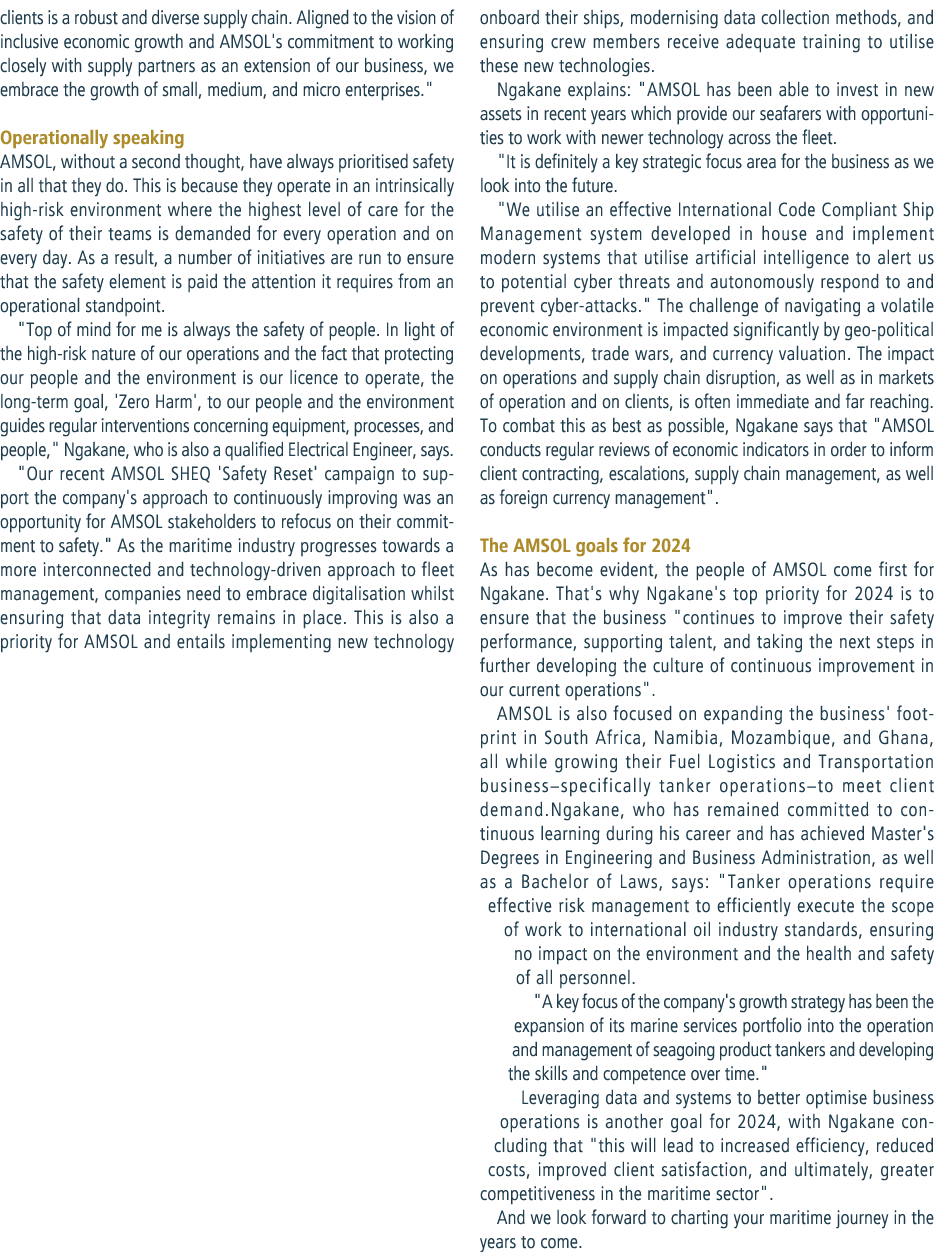

Slow pace of transformation

Although the dawn of freedom in April 1994 necessitated the introduction of a number of opportunities to advance socio-economic freedom to the people of South Africa, there is common acceptance that the following important areas of the economy remain untransformed.

- • Land distribution and restitution: The land is an important instrument for participation on the economy. It can be used as mortgage and collateral in a number of economic transactions. However, as at 2024, questions remain asked about the real and true ownership of land parcels in SA, with white people owning almost half the land. African, coloured and Indian people own a combined 46% of the land, which is largely through registered title deeds or customary trust deeds. The state is the second largest land owner.

- • Property Ownership: The value of commercial property in South Africa was estimated to be way over R1.2 trillion in 2020. Black people and practitioners owned no more than 10% of that, despite the fact that there has literally been an increase in the scale of commercial property development in black areas and communities over the last 15 years, with almost every township having a shopping complex.

The role FDIs

In an effort to acknowledge the above, the government realised the importance of starting introducing policy instruments and legislative framework to support the participation of black people in the economy. At the core of this was to encourage black people start their own businesses and not just buy stakes and shares in already existing white-owned business.

It is against this background that the likes of the IDC (which was reviewed), the DBSA (that was remodelled), the SEDA (for small businesses) and National Empowerment Fund (NEF) were established through pieces of legislation.

These were collectively known as the DFIs, the Development Funding Institutions that were meant to play a start-up and jump start role for those who were starting businesses anew.

BBBEE Enforcement and the BBBEE Commission

With the rise in the incidents of fraud, circumvention and misrepresentation of business credentials, a phenomenon referred to as FRONTING, it became necessary and important to establish an institution that would be responsible for the monitoring, investigation and even the enforcement of the BBBEE policy. The BBBEE Commission has however struggled to assert its regulatory authority due to its capacity constraints and limited regulatory authority. Such has compelled the amendment of the BBBEE Act in 2014, whose real impact is yet to be realised–10 years later.

With the passage of time, and with the BBBEE policy suffering back lashes from radical black activist organizations and critics, it became clear that there is more that needed to be done to increase the impact of what was intended by the policy. This included the introduction of the broad based approach, which would focus on indirect empowerment, such as procurement, supplier and enterprise development.

Sector focused transformation efforts

and institutional mechanism

In an effort of complimenting the implementation of BBBEE, various industries and sectors of the economy initiated sector and transformation charters intended to deal with the peculiarities of every industry and promote black participation.

The notable of these were:

The Financial Services Charter (FSC), gazetted in 2014 and committed to the achievement of at least 30% of the financial institutions in the hands of black people. Infrastructure and Developmental Finance became the major highlights of the FSC.

The Mining Charter, reviewed in 2017, would have to be used by the Department of Mineral Resources to regulate the issuing of mining licences and compel licensed mining houses to extend the mining resource beneficiation and social housing development. As of 2024, the income disparities and gaps in the mining sector remain one of the glaring and largest scandal. In 2012, over 34 miners were killed by the South African Police Service (SAPS) on 16 during a six-week labour strike and protest in the Lonmin platinum mine at Marikana, near Rustenburg whilst demanding a mere R12 500 monthly wage. Ironically, Ramaphosa was a major shareholder in the Mine and was reportedly behind the call that resulted in the pressure on the police that resulted in the massacre.

The Construction Sector Charter, gazetted in 2017 and would have accelerated entrance of black participants such as black women and emerging small scale contractors. With a 30% black ownership target, the construction industry was significantly disrupted by the Covid 19 pandemic and consequently took time and longer to recover. The slow pace of transformation in the sector has largely resulted in a community invasion phenomenon which would later be characterized as a construction mafia, largely made up of business and community individuals who disrupted infrastructure projects in return for stake and opportunities.

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, the Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB), set up over 20 years ago, has however played a rather significant role in fostering a grading system that not only promoted safety and quality of construction, but the monetary threshold that saw a number of black construction firms suddenly gaining footprint and project exposure in the infrastructure space. A sizeable number of engineering and architectural firms have even gained work opportunities in the African European markets.

The black industrialist programme: In order to leverage the State's capacity to unlock the industrial potential that exists within black-owned and managed businesses that operate within the South African economy, the government introduced the black industrialist programme that would have been targeted and well-defined financial and non-financial interventions for black people in business. The DTiC has reportedly spent at least over R 38.9 billion since the launch of the programme.

Noticeable pockets of success

It would be disingenuous to conclude that there has not been pockets of success and excellence in the participation of black people in the economy over the last 30 years. These include, but is not limited to the slight increase in the ownership and participation of black practitioners in:

- • Financial Services: African bank (30%), Capitech (15.6%), Absa bank (25%) and one time bank that is 65% owned by black management. This is a good measure of success.

- • The Middle Class: The number of black–especially black females–in the financial services and other related corporate sector of the economy has significantly increased in South Africa. The mining sector has seen the appointment of black women CEOs for the first time in the history of the mining industry over the last 15 years.

- • The property development and ownership has also seen the rise in the likes of Motseng, manaka, Billion, Masingita and Tshwese properties whose increase in the property development space was propelled by the gazette of the Property Sector Charter in 2016.

- • Inadvertently, a significant number of professionals and individuals have gained access and were able to own properties in recent times than they could be able to over 20 years ago.

In conclusion

With the dawn of the 6th administration later this year, whoever wins the elections to take control of the economic cluster, the prospects of the gains, or progress of the economic transformation gains being reversed are REAL. Only time will tell.

Thabo Masombuka is the economic transformation adviser.